Definition

A gastric bypass is a surgical procedure that creates a very small stomach; the rest of the stomach is removed. The small intestine is attached to the new stomach, allowing the lower part of the stomach to be bypassed.

Purpose

Gastric bypass surgery is intended to treat obesity, a condition characterized by an increase in body weight beyond the skeletal and physical requirements of a person, resulting in excessive weight gain. The rationale for gastric bypass surgery is that by making the stomach smaller a person suffering from obesity will eat less and thus gain less weight. The operation restricts food intake and reduces the feeling of hunger while providing a sensation of fullness (satiety) in the new smaller stomach.

Demographics

Obesity affects nearly one-third of the adult American population (approximately 60 million people). The number of overweight and obese Americans has steadily increased since 1960, and the trend has not slowed down in recent years. Currently, 64.5% of adult Americans (about 127 million) are considered overweight or obese. Each year, obesity contributes to at least 300,000 deaths

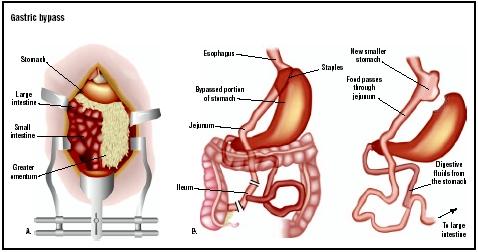

In this Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, a large incision is made down the middle of the abdomen (A).The stomach is separated into two sections. Most of the stomach will be bypassed, so food will no longer go to it. A section of jejunum (small intestine) is then brought up to empty food from the new smaller stomach (B). Finally, the surgeon connects the duodenum to the jejunum, allowing digestive secretions to mix with food further down the jejunum. (Illustration by GGS Inc.)in the United States, with associated health-care costs amounting to approximately $100 billion.

In the United States, obesity occurs at higher rates in such racial or ethnic minority populations as African American and Hispanic Americans, compared with Caucasian Americans and Asian Americans. Within the minority populations, women and persons of low socioeconomic status are most affected by obesity.

Description

Several types of malabsorptive procedures, meaning procedures that are intended to lower caloric intake, may be used to perform gastric bypass surgery, including:

- gastric bypass with long gastrojejunostomy

- Roux-en-Y (RNY) gastric bypass

- transected (Miller) Roux-en-Y bypass

- laparoscopic RNY bypass

- vertical (Fobi) gastric bypass

- distal Roux-en-Y bypass

- biliopancreatic diversion

All procedures aim to restrict food intake and differ in the surgical approach used to create a smaller stomach. Choice of procedure relies on the patient’s overall health status and on the surgeon’s judgement and experience.

In the operating room , the patient is first put under general anesthesia by the anesthesiologist. Once the patient is asleep, an endotracheal tube is placed through the mouth of the patient into the trachea (windpipe) to connect the patient to a respirator during surgery. A urinary catheter is also placed in the bladder to drain urine during surgery and for the first two days after surgery. This also allows the surgeon to monitor the patient’s hydration. A nasogastric (NG) tube is also placed through the nose to drain secretions and is typically removed the morning after surgery.

In most clinics and hospitals, the operation of choice for obese people is the RNY gastric bypass, which has the endorsement of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The surgeon starts by creating a small pouch from the patient’s original stomach. When completed, the pouch will be completely separated from the remainder of the stomach and will become the patient’s new stomach. The original stomach is first separated into two sections. The upper part is made into a very small pouch about the size of an egg that can initially hold 1–2 oz (30–60 ml), as compared to the 40–50 oz (1.2–1.5 l) held by a normal stomach. It is created along the more muscular side of the stomach, which makes it less likely to stretch over time. This procedure will allow food to proceed from the mouth to the esophagus, into the gastric pouch, and then immediately into the part of the small bowel called the jejunum (or Roux limb). Food no longer goes to the larger portion of the stomach. Because none of the original stomach is removed, its secretions can travel to the duodenum. The two parts of the stomach are thus completely separated and are closed by stapling and sewing to eliminate the possibility of leaks. Scar tissue eventually forms at the stapled and sewn area so that the pouch and stomach are permanently separated and sealed. Finally, the surgeon reconnects the first part of the jejunum and the duodenum containing the juices from the stomach, pancreas, and liver (the biliopancreatic limb) to the segment of small bowel that was connected to the gastric pouch (the Roux limb).

The opening between the new stomach and the small bowel is called a stoma. It has a diameter of some 0.31 in (0.8 cm). All food goes into the new small stomach and must then pass through this narrow stoma before entering the small intestine. The part of the small intestine from the upper functioning small stomach and the part of the small intestine from the initial lower stomach are joined in a Y connection so that the gastric juices can mix with the food coming from the small pouch.

The RNY can also be performed laparoscopically. The result is the same as an open surgery RNY, except that instead of opening the patient with a long incision on the stomach, surgeons make a small incision and insert a pencil-thin optical instument, called a laparoscope, to project a picture to a TV monitor. The laparoscopic RNY results in smaller scars, and usually only three to four small incisions are made. The average time required to complete the laparoscopic RNY gastric bypass is approximately two hours.

Diagnosis/Preparation

A diagnosis of obesity relies on the patient’s medical history and on a body weight assessment based on the body mass index (BMI) and on waist circumference measurements. According to the American Obesity Association (AOA), a BMI greater than 25 defines overweight and marks the point where the risk of disease increases from excess weight. A BMI greater than 30 defines obesity and marks the point where the risk of death increases from excess weight. Waist circumference exceeding 40 in (101 cm) in men and 35 in (89 cm) in women increases disease risk. Gastric bypass as a weight loss treatment is considered only for severely obese patients.

To prepare for surgery, the patient is asked to arrive at the hospital a few hours before surgery. While in the preoperative holding room, the patient meets the anesthesiologist who explains the procedure and answers any questions. An intravenous (IV) line is placed, and the patient may be given a sedative to help relax before going to the operating room.

Aftercare

In most cases, gastric bypass is a patient-friendly operation. Patients experience postoperative pain and such other common discomforts of major surgery, as the NG tube and a dry mouth. Pain is managed with medication. A large dressing covers the surgical incision on the abdomen of the patient and is usually removed by the second day in the hospital. Short showers 48 hours after surgery are usually allowed. Patients are also fitted with Venodyne boots on their legs to massage them. By squeezing the legs, these boots help the blood circulation and prevent blood clot formation. At the surgeon’s discretion, some patients may have a gastrostomy tube (g-tube) inserted during surgery to drain secretions from the larger bypassed portion of the stomach. After a few days, it will be clamped and will remain closed. When inserted, the g-tube usually remains for another four to six weeks. It is kept in place in the unlikely event that the patient may need direct feeding into the stomach. By the evening after surgery or the next day at the latest, patients are usually able to sit up or walk around. Gradually, physical activity may be increased, with normal activity resuming three to four weeks after surgery. Patients are also taught breathing exercises and are asked to cough frequently to clear their lungs of mucus. Postoperative pain medication is prescribed to ease discomfort and initially administered by an epidural. By the time patients are discharged from the hospital, they will be given oral medications for pain. Patients are not allowed anything to eat immediately after surgery and may use swabs to keep the mouth moist. Most patients will typically have a three-day hospital stay if their surgery is uncomplicated.

Postoperative day 1

The NG tube is removed in the morning after surgery. The patient is allowed sips of water throughout the day. The patient is assisted to get out of bed and encouraged to walk. It is very important to walk as early after surgery as possible to help prevent pneumonia, blood clots in the legs, and constipation.

Postoperative day 2

If the patient has tolerated water intake on day 1, he or she may begin taking clear liquids. Patients are encouraged or helped to walk in the hallways at least three times a day and are encouraged to use the breathing machine. The urinary catheter is removed from the bladder. Patients given oral pain medications, crushed, chewed, or in liquid form.

Postoperative day 3

Patients are advanced to a more substantial diet that usually includes milk-based liquids. When the diet is tolerated, pain is well controlled on oral pain medication, and patients are able to walk independently, they are discharged from the hospital. A dietitian usually visits the patient prior to discharge to review any questions about diet. Although most patients spend three days in the hospital, they may remain longer if they have postoperative nausea, fevers, or weakness.

Additional tests are performed at a later stage to ensure that there have been no surgical complications. For example, a swallow study may be performed to make sure that there is no leak where the pouch and intestines have been joined together. Sometimes chest x rays are also performed to make sure that there are no signs of pneumonia. Blood tests may be required. These and other postoperative tests are performed on an individual basis as determined by the surgical team .

Risks

Gastric bypass surgery has many of the same risks associated with any other major abdominal operation. Life-threatening complications or death are rare, occurring in fewer than 1% of patients. Such significant side effects as wound problems, difficulty in swallowing food, infections, and extreme nausea can occur in 10–20% of patients. Blood clots after major surgery are rare but extremely dangerous, and if they occur may require re-hospitalization and anticoagulants (blood thinning medication).

Some risks, however, are specific to gastric bypass surgery:

- Dumping syndrome. Usually occurs when sweet foods are eaten or when food is eaten too quickly. When the food enters the small intestine, it causes cramping, sweating, and nausea.

- Abdominal hernias. These are the most common complications requiring follow-up surgery. Incisional hernias occur in 10–20% of patients and require follow-up surgery.

- Narrowing of the stoma. The stoma, or opening between the stomach and intestines, can sometimes become too narrow, causing vomiting. The stoma can be repaired by an outpatient procedure that uses a small endoscopic balloon to stretch it.

- Gallstones. They develop in more than a third of obese patients undergoing gastric surgery. Gallstones are clumps of cholesterol and other matter that accumulate in the gallbladder. Rapid or major weight loss increases a person’s risk of developing gallstones.

- Leakage of stomach and intestinal contents. Leakage of stomach and intestinal contents from the staple and suture lines into the abdomen can occur. This is a rare occurrence and sometimes seals itself. If not, another operation is required.

Because of the changes in digestion after gastric bypass surgery, patients may develop such nutritional deficiencies as anemia, osteoporosis, and metabolic bone disease. These deficiencies can be prevented by taking iron, calcium, Vitamin B 12 , and folate supplements. It is also important to maintain hydration and intake of high-quality protein and essential fat to ensure healthy weight loss.

Normal results

In the years following surgery, patients often regain some of the lost weight. But few patients regain it all. Of course, diet and activity level after surgery also play a role in how much weight a patient may ultimately lose. Results from long-term follow-up data of gastric bypass surgery show that over a five-year period, patients lost 58% of their excess weight. Over 10 years, the loss was 55%, and after 14 years, excess weight loss was 49%. While there is a tendency to slowly regain some of the lost weight, there is still a significant permanent weight loss over a long period of time.

Morbidity and mortality rates

Obesity by itself does not cause death. However, for those with a body mass index (BMI) above 44 lb/m 2 (20 kg/m 2 ), morbidity for a number of health conditions will increase as the BMI increases. (M 2 refers to the percent of body fat divided by height). Higher morbidity, in association with overweight and obesity, has been reported for hypertension, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, stroke, gallbladder disease, osteoarthritis, sleep apnea and respiratory problems, and some types of cancer (endometrial, breast, prostate, and colon). Obesity is also associated with complications of pregnancy, menstrual irregularities, hirsutism, stress incontinence, and psychological disorders (depression).

Alternatives

Surgical alternatives

The Lap-Band gastric restrictive procedure represents an alternative to gastric bypass surgery. The Lap-Band offers another approach to weight loss surgery for patients who feel that a gastric bypass is not suitable for them. It causes weight loss by lowering the capacity of the stomach, thus restricting the amount of food that can be eaten at one time. The band is fastened around the upper stomach to create a new tiny stomach pouch. As a result, patients experience a sensation of fullness and eat less. Since there is no cutting, stapling, or stomach rerouting involved, the procedure is considered the least invasive of all weight loss surgeries. The surgeon makes several tiny incisions and uses long slender instruments to implant the band. By avoiding the large incision of open surgery, patients generally experience less pain and scarring. In addition, the hospital stay is shortened to less than 24 hours, including overnight hospitalization.

Vertical banded gastroplasty (VBG), another commonly used surgical technique also known as stomach stapling, is today considered inferior to RNY gastric bypass in inducing weight loss. It is also associated with several undesirable complications.

Non-surgical alternatives

Dietary therapy is the fundamental non-surgical alternative. It involves instruction on how to adjust a diet to reduce the number of calories eaten. Reducing calories moderately is known to be essential to achieve gradual and steady weight loss and also to be important for maintenance of weight loss. Strategies of dietary therapy include teaching patients about the calorie content of different foods, food composition (fats, carbohydrates, and proteins), reading nutrition labels, types of foods to buy, and how to prepare foods. Some diets recommended for weight loss include low-calorie, very low-calorie, and low-fat regimes.

Another nonsurgical alternative is physical activity. Moderate physical activity, progressing to 30 minutes or more on most or preferably all days of the week, is recommended for weight loss. Physical activity has also been reported to be a key part of maintaining weight loss. Abdominal fat and, in some cases, waist circumference can be modestly reduced through physical activity. Strategies of physical activity include the use of such aerobic forms of exercise as aerobic dancing, brisk walking, jogging, cycling, and swimming and selecting enjoyable physical activities that can be scheduled into a regular routine.

Behavior therapy aims to improve diet and physical activity patterns and habits to new behaviors that promote weight loss. Behavioral therapy strategies for weight loss and maintenance include recording diet and exercise patterns in a diary; identifying such high-risk situations as having high-calorie foods in the house and consciously avoiding them; rewarding such specific actions as exercising for a longer time or eating less of a certain type of food; modifying unrealistic goals and false beliefs about weight loss and body image to realistic and positive ones; developing a social support network (family, friends, or colleagues); or joining a support group that can encourage weight loss in a positive and motivating manner.

Drug therapy is another nonsurgical alternative recommended as a treatment option for obesity. Three weight loss drugs been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating obesity: orlistat (Xenical), phentermine, and sibutramine (Meridia).

Resources

books

Flancbaum, L. The Doctor’s Guide to Weight Loss Surgery. New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Pub., 2003.

Thompson, B. Weight Loss Surgery: Finding the Thin Person Hiding Inside You. Tarentum, PA: Word Association Publishers, 2002.

Woodward, B. G. A Complete Guide to Obesity Surgery: Everything You Need to Know About Weight Loss Surgery and How to Succeed. New Bern, NC: Trafford Pub., 2001.

periodicals

Al-Saif, O., S. F. Gallagher, M. Banasiak, S. Shalhub, D. Shapiro, and M. M. Murr. “Who Should Be Doing Laparoscopic Bariatric Surgery?” Obesity Surgery 13 (February 2003): 82–87.

Livingston, E. H., C. Y. Liu, G. Glantz, and Z. Li. “Characteristics of Bariatric Surgery in an Integrated VA Health Care System: Follow-Up and Outcomes.” Journal of Surgical Research 109 (February 2003): 138–143.

Patterson, E. J., D. R. Urbach, and L. L. Swanstrom. “A Comparison of Diet and Exercise Therapy versus Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass Surgery for Morbid Obesity: A Decision Analysis Model.” Journal of the American College of Surgeons 196 (March 2003): 379–384.

Rasheid, S., et al. “Gastric Bypass Is an Effective Treatment for Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Patients with Clinically Significant Obesity.” Obesity Surgery, 13 (February 2003): 58–61.

organizations

American Obesity Association. 1250 24th Street, NW, Suite 300, Washington, DC 20037. (202) 776-7711. http://www.obesity.org .

American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 7328 West University Avenue, Suite F, Gainesville, FL 32607. (352) 331-4900. http://www.asbs.org .

“Laparoscopic Gastric Bypass Surgery.” Gastric Bypass Home-page. [cited June 2003] http://www.lgbsurgery.com/ .

“The Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass.” Advanced Obesity Surgery Center. [cited June 2003] http://www.advancedobesitysurgery.com/gastric_bypass.htm .

Monique Laberge, PhD